MAY 2018: RACE MATTERS

Race: obvious, elusive, divisive, ubiquitous. Half-a-millennium ago, it was an unknown concept. Yes, people noticed surface differences among various populations back then. But the notion of “race” as a definer of inherent group qualities only began when Europeans overran and colonized the rest of the world, and passed judgment on the people they encountered. Those judgments continue to influence attitudes and behavior to this day. Despite dreams of a “post-racial” society, there appears to be no end in sight to our obsession with the color of people’s skin.

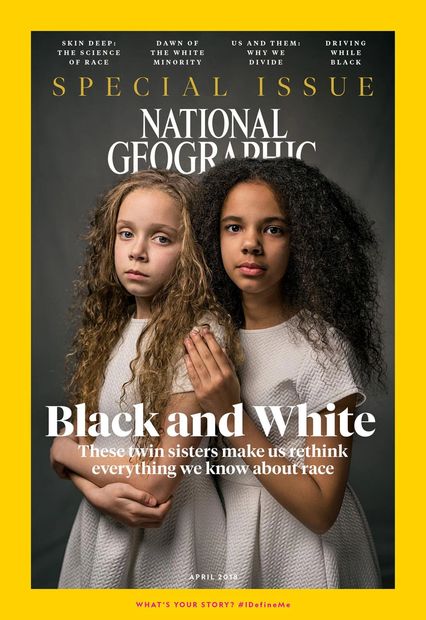

The April edition of the venerable National Geographic magazine devotes its entire contents to questions of race: What is it, really? Is it relevant, or even necessary? Can we learn to live without it? Or are we doomed to repeat history indefinitely?

On the cover of the issue is a photo of a pair of 11-year-old fraternal-twin sisters. One of the girls has fair skin and blond hair. The other is darker-skinned and has black hair. Their father is black. Their mother is white. The girls’ facial features are so similar that if the sisters were of the same complexion, they could be mistaken for identical twins rather than fraternal.

The girls provide an indication that “race” is not as cut-and-dried as it may seem at first glance. The rest of this issue reinforces that point.

Conventional wisdom tells us that racial characteristics such as skin color emerged as adaptations to the various climate conditions that human forebears encountered during their migrations out of – and within – the ancestral continent of Africa. Darker skin, for example, reduces the effects of cancer-causing ultraviolet rays from tropical sunshine. Lighter skin enhances the effects of Vitamin D, which prevents ailments such as rickets, a childhood bone disease.

And yet … black people have lived and thrived in northern countries such as Norway and Sweden. And fair skin has not precluded white people from living in sun-swept countries such as Australia and South Africa.

An article titled “Skin Deep” by Elizabeth Kolbert traces the history of the scientific study of racial differences from the early 19th century, when skull measurements were employed to support the alleged “superiority” of the Caucasian race, to modern studies of DNA and the human genome, which suggests that visible differences are superficial in comparison with internal factors such as blood type, resistance to certain diseases, and lactose intolerance. Kolbert concludes that “race” is more social construct than biological actuality. Yet it’s the social construct that prevails, even as modern science continues to debunk it.

A photo feature, “The Things That Divide Us,” further demonstrates the potency of the race construct. From the contrast of leafy suburbs and impoverished townships in South Africa; to marches and counter-marches in Charlottesville, Virginia; to co-existence between Tutsis and Hutus in post-genocidal Rwanda; to the proposed border wall between the United States and Mexico – the consequences of the construct are plain to see. Yet the current state of peace in Rwanda suggests that those consequences are not necessarily immutable.

A feature on interracial marriage, however, furnishes further evidence of the erosion of at least some aspects of the construct. There was a time, not so long ago, when “mixed marriages” were not only frowned upon, but also outlawed in some jurisdictions. No longer. Although interracial marriage used to primarily refer to unions between whites and blacks, “The Many Colors of Matrimony” showcases wedding photos of an African-American bride and a Turkish groom; a white American bride and a South Asian groom; a Chinese bride and a white American groom – and a black groom and a white groom.

“The Rising Anxiety of White America,” by Michele Norris, is likely to be the most controversial article in the issue. After a two-century tenure as the dominant majority population of the United States (not to mention Canada), demographers expect whites to become a minority in the U.S. by the middle of this century. This prospect triggers anxiety in some people – and outright terror in others. That fear was made manifest in the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States in 2016.

The status quo position of dominance has been under siege for decades. An increase in non-white immigration combined with the inroads minority-group members – especially blacks – in many areas, combined with the massive loss of manufacturing jobs to foreign countries and automation, has undermined assumptions of superiority. The straw that broke that camel’s back was the election and re-election of Barack Obama as the first black President in 2008 and 2012. Widespread joy greeted Obama’s election victories. But not everyone was happy.

Norris shows how the construct of race causes those whites who base their identity and self-esteem on an assumption of racial superiority (and not all of them do) to lash out at the most visible and convenient targets when that assumption is threatened. Apparently, belief in racial superiority and supremacy is very, very hard to give up. Until that belief becomes obsolete, misuse of the construct of race will persist. The poisoned tree will continued to bear its bitter fruit.

Were it not for the article on white anxiety, a feature called “The Stop” by Michael A. Fletcher would have taken first prize for controversy. It delves into the fraught relationship between police and minorities, especially blacks. It’s not just about the spate of fatal police shootings of black men. It’s also about the grinding indignity of being stopped for street checks, or for driving a new car in the “wrong” neighborhood. This, among many other factors, creates fear and anxiety among blacks and Hispanics. No wonder, when the ones who are supposed to protect you act as though you are the enemy in an undeclared war.

“A Place of Their Own,” by Clint Smith, looks at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in the U.S. These institutions began their existence during the latter half of the 19th century. At that time, white institutions of higher learning accepted only a handful of black students, and often none at all. Black institutions were founded to provide that vital post-secondary education. They produced such luminaries as Martin Luther King, Jr.

These days, there’s been something of a pushback against HBCUs, with some critics dismissing them as relics of segregation and threatening to revoke their charters and curtail their funding. Yet Smith points out that enrolment at HBCUs is increasing rather than dwindling. But … are HBCUs really segregated?

Full disclosure: I went to an HBCU, Lincoln University of Pennsylvania, during the 1960s. This year marks the 50th anniversary of my class’ graduation. Back then, a small number of whites attended Lincoln. About half the faculty and administration were white, as was the university’s president. We even had a student from Taiwan. The school was far from segregated, then or now.

As long as HBCUs continue to open their doors to students and staff of all ethnicities, there is no justification in calling for their shutdown simply because they are historically black in origin.

The issue ends on a note of creativity, with a series of images from an African artist’s photographic interpretations of key events in African-American history, ranging from the 1965 voting-rights march in Selma, Alabama, to the 2012 shooting death of teenager Trayvon Martin.

If nothing else, the National Geographic special clearly demonstrates that race – both as a social construct and subject for scientific study – still matters.

Perhaps a day will come when it no longer does. That would be a fitting subject for a future National Geographic special issue.