what's in a team name

The names, logos and mascots of certain professional sports franchises have served as a bitter battleground in the culture wars that have raged since the 1960s. Names such as “Indians,” Redskins,” and “Chiefs” are flashpoints for acrimonious disputes between those who consider those designations to be racist and offensive, and those who dismiss the critics’ concerns as hypersensitive or instances of political correctness gone wild. That impasse has been entrenched for decades – until now.

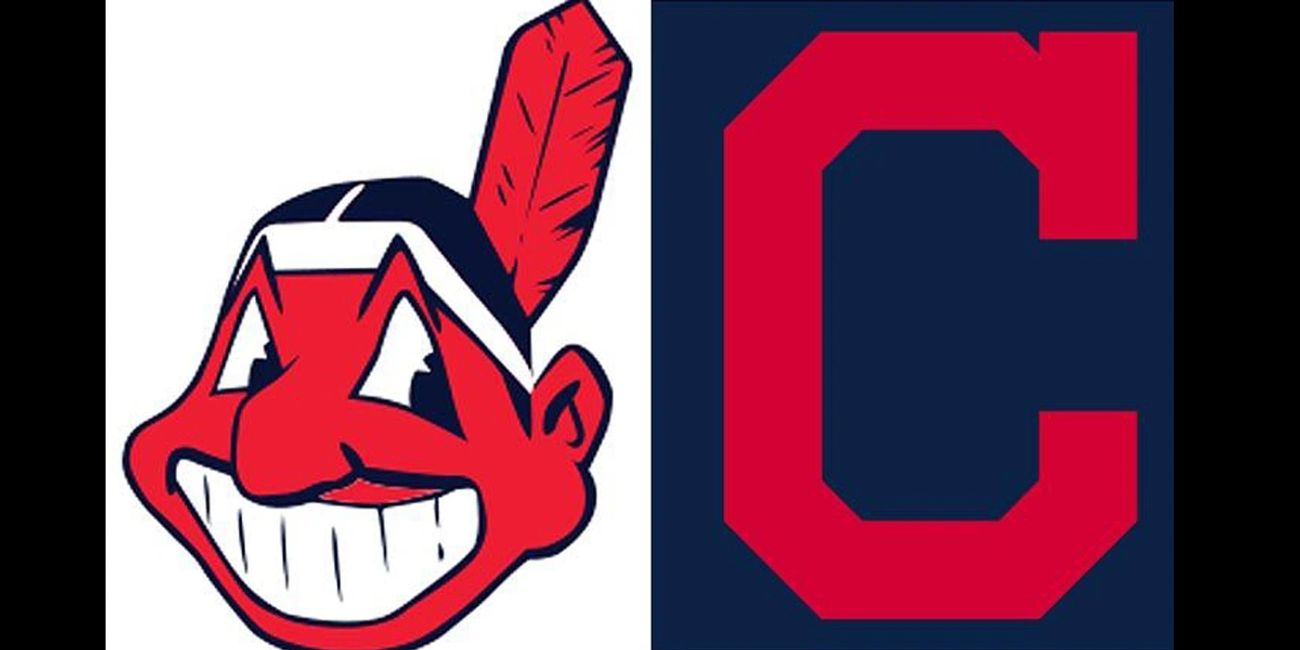

Recently, the Cleveland Indians Major League Baseball team announced that it is dropping its long-time logo – “Chief Wahoo,” a grinning, scarlet-faced caricature of a Native American – and replacing it with a block-letter capital “C”. The franchise will, however, retain its name, which is a point of contention in its own right.

The baseball team’s decision to change its logo is a crack in the impasse. Is this development just an anomaly? Or is it the forerunner of further changes to come? Only time will tell.

Either way, the debates and disputes will continue. Even so, there are ways to change controversial team names and logos that can potentially minimize the angst that usually accompanies the matter. All it takes is s a bit of lateral thinking.

Here are some suggestions …

CLEVELAND INDIANS

The baseball team’s ouster of “Chief Wahoo” is welcome. But the name “Indians” perpetuates a misnomer that has persisted for more than half-a-millennium. When European explorers stumbled into the continents of North and South America, they thought they had reached the “Indies,” or lands and islands located in the Indian Ocean. So they called the inhabitants of the new (to them) lands “Indians.” It didn’t take long for the Europeans to realize that the two continents were neither India nor the Indies, but the initial misnomer stuck, and endures to this day.

If Cleveland fans prove to be willing to forgo “Chief Wahoo,” but are reluctant to let go of the “Indians” name, a compromise is available – one that involves the logo. Instead of a capital “C”, which could just as easily stand for Chicago or Cincinnati or California, why not use an outline map of India? That way, the true Indians would be recognized without resorting to some caricature that could be deemed offensive.

WASHINGTON REDSKINS

This venerable NFL football franchise bears the distinction of being the granddaddy of all name and logo controversies. Disputes over this team, located in the capital city of the United States, has been red-hot (no pun intended) for decades. The battle lines are clearly drawn. The fury that boils on both sides of the issue is intense. Yet there is a relatively simple alternative that could abate the anger.

First, some background. The use of the term “redskins” to describe Native Americans is yet another misnomer, again dating back to the European “discovery” of the Americas.

Like some people in other parts of the world, certain Native American ethnic groups smeared their bodies with red ocher for ceremonial and other purposes. Hence, the “red skin” perception. Once the Native Americans washed the ochre away, the Europeans could easily see that the people’s skin was not really red. But again the initial misperception continued, whether the Native Americans liked it or not.

Yet there are people in the world whose epidermis is indeed red, though temporarily and under specific circumstances. Go to any beach at the beginning of summer, and you will see lots of fair-skinned Caucasians sporting sunburns that turn their bodies as red as a brick or a boiled lobster.

The current logo of the Washington team is a befeathered profile of Native American with a red-bronze cast to this skin. Now, substitute the head of a sunburned white man for that of the Native American, and voila! You’ve got a person with a red skin, and the whole question of whether or not the name offends Native Americans or anyone else disappears.

ATLANTA BRAVES

Usually, “brave” is a positive word, associated with courage and valor. At some point in the past, European settlers in North America turned the word “brave” from an adjective to a noun, applying it to the Native American warriors against whom they often fought. As time passed, the concept “Indian brave” became part of a grab-bag of stereotypes pertaining to Native Americans, and its initial positive connotations eroded.

In the meantime, a baseball franchise that began its operations in Boston during the late 19th century called itself the “Braves.” Through subsequent moves to Milwaukee, and then Atlanta, the franchise retained its name. Its logo has evolved into the image of a tomahawk, a weapon favored by eastern Native nations in earlier times. But both the name and the logo have fallen out of favor with some critics, accompanied by pushback from others who are offended by the critics’ complaints.

A change in both name and logo could end those complaints. The name “Braves” could be changed to “Bravehearts,” in homage to the classic movie about Scottish Highlanders battling British invaders. And instead of a tomahawk, the weapon in the logo could be a claymore sword. Nothing to be offended about there.

KANSAS CITY CHIEFS

The term “chief,” which is derived from the French word chef, has both general and specific applications. Generally, a “chief” is the designated leader of supervisor of an organization such as a police or fire department. In the navy, there is a rank called “chief petty officer.” In a media newsroom, the holder of the top job is the “editor-in-chief.” The term is also employed to describe the head of a tribal society, particularly in Africa and the Americas. That’s where the trouble begins. Native American individuals are often called “chief,” whether they actually are one or not. Used in that manner, the term becomes derogatory rather than definitive.

The name and logo of the NFL’s Kansas City Chiefs are both connected to Native Americans. The team’s logo is an arrowhead with the word “Chiefs” written inside its outline. At least there’s no caricatured image of a Native American here. Still, an alternative would be preferable. Fortunately, there is one.

In the time before Jackie Robinson integrated Major League Baseball, there was a team called the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro Leagues, which existed only because blacks were barred from playing in MLB. Transferring that name to the football franchise would honor the Monarchs’ legacy, even though that team played a different sport. Serendipitously, Robinson played for the Monarchs before Brooklyn Dodgers signed him to an MLB contract. A crown similar to, but not exactly like, that of the Kansas City Royals baseball team could be the logo of the football Monarchs. Such a change would be a tribute to the past and a signpost to the future.

CHICAGO BLACKHAWKS

This storied National Hockey League franchise, winners of several Stanley Cups, was named after the chief (there’s that word again) of a Native American nation that dwelled in the Midwest. Its logo is a profile of a Native American’s head, with an orange-ish skin tone and the requisite feathers festooning his hair. Although the logo is not renders as a Chief Wahoo-style cartoon, it still represents a stereotyped image of Native Americans, and is therefore problematic.

Fortunately, there is a quick and easy way solve that problem, with no need to rename the franchise. There is a species of North American bird called – you guessed it – the blackhawk. A simple substitution of the bird of prey’s head for that of the Native American would quell whatever objections there are to the current logo, and allow the team to keep its name without objection.

EDMONTON ESKIMOS

When this Canadian Football League franchise was founded, “Eskimo” was the conventional term of reference for the Native American people who live in the Far North of Canada and Alaska. However, that was not the name by which they refer to themselves. The preferred term is “Inuit,” which gradually superseded “Eskimo” over the past few decades. Yet the football team continues to use the outdated term.

Even among the Inuit, opinions are divided as to whether the “E-word” is offensive. Criticism over the football team’s name is not as intense as the furor over “Indians” and “Redskins.” And there’s no contention at all over the team’s logo, which consists of a pair of capital “E’s”. So this is one Native North American team name that has largely escaped the culture wars, and no changes seem necessary at this time.

GOLDEN STATE WARRIORS

“Warrior” is a generic term used primarily to describe an armed combatant from a tribal society, as opposed to a soldier from a nation-state. The definition of the term has expanded to encompass anyone – man or woman – who demonstrates courage under extenuating circumstances.

Like many teams in many sports at all levels from professional leagues to elementary school, the 2016-2017 National Basketball Association champions go by the “Warriors” name. Unlike some of those teams, however, Golden State does not use a Native American image as its logo. But it once did, in an earlier incarnation.

Though they are now based in San Francisco, the Warriors’ original home was Philadelphia. During the 1950s and early 1960s, the Philadelphia Warriors’ logo was a grinning, caricatured Native American who was dribbling a basketball. When the team moved to San Francisco in 1962, it replaced the caricature with a drawing of a feathered headdress. Later, the San Francisco Warriors became the Golden State Warriors, and it changed its logo to a drawing of the iconic Golden Gate Bridge. This is one case of a major sports franchise that got it right well before the current culture wars erupted.

The team-name wars are bound to continue. But they don’t have to last forever. Either/or standoffs are not the only alternative. A little thinking outside the box can go a long way, as was the case with the Golden State Warriors.